‘We heard the call’:

50 years on, Haydenville man continues fight against voter suppression

By LUIS FIELDMAN

Staff Writer • Daily Hampshire Gazette • Northampton, MA • contact: lfieldman@gazettenet.com

Saturday, October 6, 2018

At 19, Jim Lemkin found himself in an old pickup truck on a bumpy, winding road in rural Mississippi at the height of the Civil Rights Movement.

He was riding with Mr. Ball, an elderly black man who was Lemkin’s host on a voting rights mission to the South, and Mr. Ball pointed to a switch on his dashboard.

“You know what this is about?” Mr. Ball asked.

Lemkin replied he didn’t know.

“It turns off the taillights, so when the Ku Klux Klan is chasing you at night you can lose them,” Mr. Ball said.

Weeks earlier, Lemkin, a sophomore at the University of Rochester at the time, had noticed a poster calling for volunteers to drive to Mississippi to help register black voters for the first time. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 had recently passed, and many of the discriminatory voting practices used in the South were outlawed by President Lyndon Johnson.

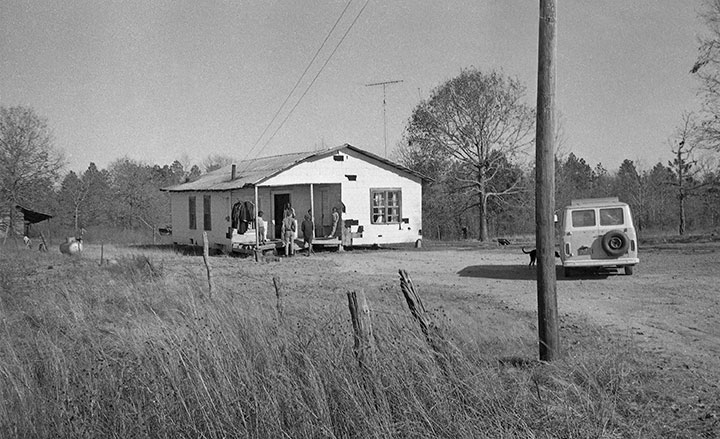

Lemkin hopped into a van with five other college students from Boston and New York, and they drove to Tylertown, Mississippi, as part of an effort to spread the word to the African-American community that voter suppression tactics had become illegal.

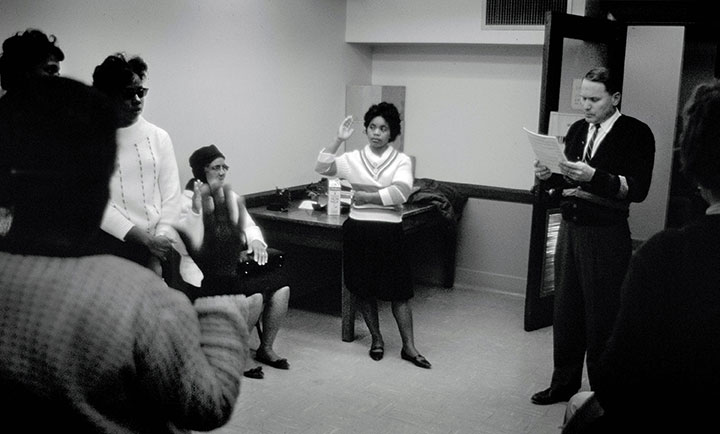

Over the course of his winter break, from mid-December 1965 to mid-January 1966, Lemkin documented the group’s mission — called Mississippi Freedom Christmas — through photographs portraying young, northern college students meeting black southerners on the front steps of their homes and informing them about their rights guaranteed by the newly signed federal law.

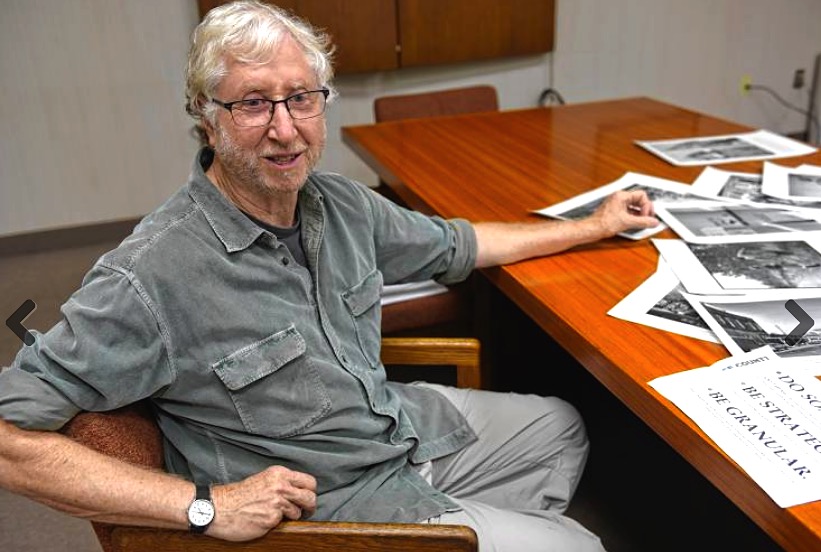

“We heard the call, each in our own way,” Lemkin, 71, of Haydenville, said at a public discussion, “Does My Voice Count? Voter Suppression Then and Now,” held at Forbes Library last week.

He acknowledged that most of the volunteer students came from privileged backgrounds, but that their work still carried a certain amount of risk in the face of resentment and hostility toward black citizens exercising their right to vote.

When they got to Mississippi, Lemkin said he was “shocked” to find that segregation persisted years after Supreme Court rulings of the mid-1950s had struck down the “separate but equal” doctrine. On a visit to the Statehouse, there were signs of a “White Only” water fountain prominently on display.

“It was illegal, but there was no one enforcing the laws,” Lemkin said.

“Within almost no time, everyone knew who we were because we were driving the only van with New York license plates and word gets out very fast,” he said.

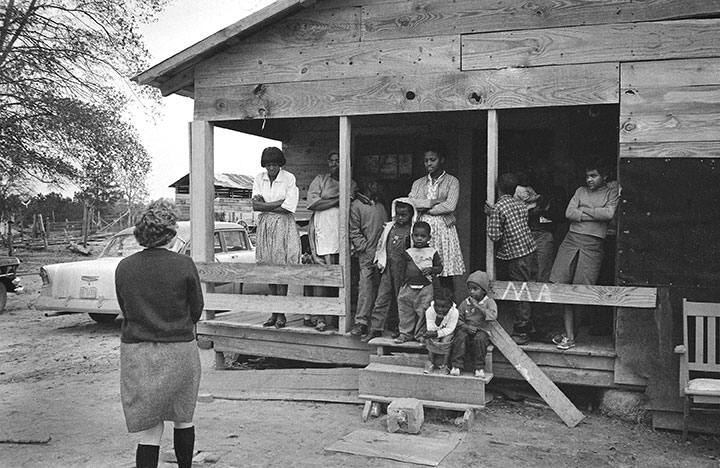

Lemkin and his group would travel the old country roads going from house to house as part of their information campaign, he said, some of which were sharecropper’s shacks.

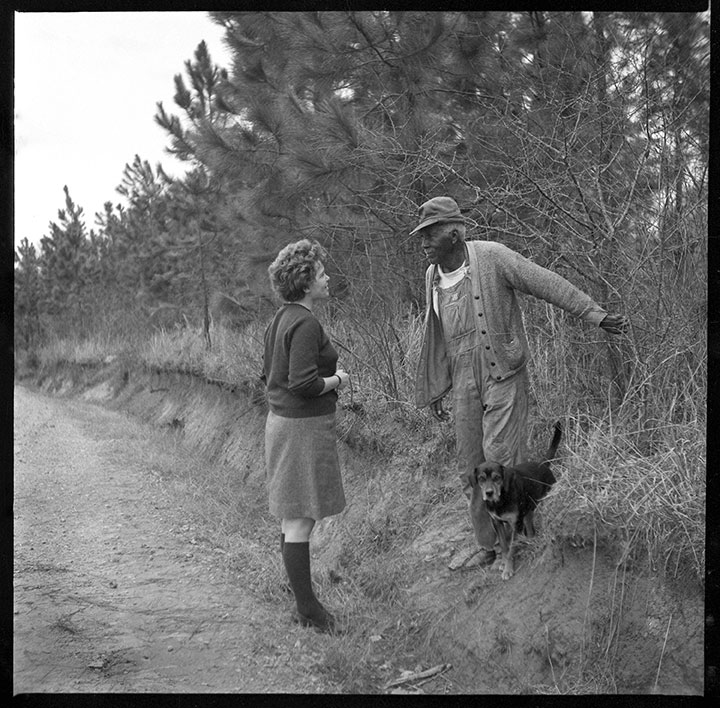

“We stopped people along the road to tell them that they could vote, and if they needed a ride, we could do that,” Lemkin said.

Many of Lemkin’s photographs — which are on display at Forbes until Oct. 13 — capture these historic moments as elderly African-American men and women registered to vote for the first time in their lives. Others show the college students speaking with southern blacks unaccustomed to white visitors.

Lemkin said that local black churches had notified African-American residents that college students would be visiting their communities. Still, he noted that for African-Americans, “a white man walking up to their house often didn’t mean anything good.”

“When we came up to them with open hearts, it made a huge difference,” Lemkin said. “We came with a clear intention of wanting to help.”

Coordinated response

Participating college students received training upon arrival to their assigned towns on how to navigate the sensitive color line of the South. Through orientations held by the mission’s organizers in local black churches, volunteers were told to avoid going into black people’s homes, as well as how to interpret body language. They even learned self-defense tactics to use, if necessary, against “irate white folk,” according to Lemkin.

The year before, three activists working as part of the Freedom Summer campaign to register to vote African-Americans in Mississippi were murdered in Neshoba County. Their names were James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner.

An investigation by the FBI, local and state authorities, found that members of the Ku Klux Klan, the Neshoba County Sheriff’s Office, and the Police Department in Philadelphia, Mississippi, were involved in the incident.

The National Student Association, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, and the Congress of Racial Equality organized the effort to enroll voters across southern states. Within two years of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the number of eligible voters jumped from six percent to 60 percent in Mississippi, according to U.S. Commission for Civil Rights.

The contributions by college student volunteers “were just one point of light among thousands,” Lemkin said, noting that most efforts were led by black people.

Prior to the signing of the Voting Rights Act on Aug. 6, 1965, states could impose their own disfranchising laws — such as poll taxes, literacy tests, and vouchers of “good character” — without pre-approval of the federal government. Many of these state laws began to be enacted during the 1890s, according to the United States Department of Justice.

Even though the 15th Amendment was ratified in 1870, providing the right to vote regardless of race or color, violence on behalf of the Ku Klux Klan and other terrorist organizations, along with voter suppression laws, resulted in suppressed black voter turnout.

With the passing of the Voting Rights Act, federal examiners were conducting voter registrations across the country, and black voter registration began to sharply rise.

Renewed mission

In September 2017, Lemkin was rummaging through a trunk in his basement when he came across an envelope with “Mississippi 1965” written on it. Inside were the film negatives of the photographs he took in Mississippi nearly 53 years ago.

He spent the next two months restoring the photographs, and after showing them to some friends, he decided he wanted to bring to attention to how voting laws have changed over the past half century.

“We know the political system is sick, we know the medical system in our country is sick, we know economic systems in our country are sick,” he said during an interview with the Gazette.

Since 1981, Lemkin has practiced naturopathic medicine in the Pioneer Valley. In 1984, he founded Pioneer Nutritional Formulas, which produces vitamin, mineral and herbal supplements.

He uses natural approaches that work with the body’s own self-healing abilities to treat for all kinds of conditions, he said. For the past few years, he has begun to wind down his practice in Shelburne Falls, and he is now starting to apply his naturopathic medicine philosophy to his work as a voting rights activist.

By using his experience as a naturopathic doctor, he said he is seeking “healing solutions” for those issues.

“There are principles of healing that can be applied in a very broad, holistic way to help see what is really going on in any organism at all,” Lemkin said.

He is applying those principals by hosting public discussions that encompass his 1965 trip to Mississippi as well as informing audiences about the 2013 Supreme Court decision, Shelby v. Holder, which struck down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act.

The ruling meant that states no longer needed preapproval from the federal government to change their voter registration laws, which were often referred to as preclearences.

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who wrote the dissenting opinion on the 5-4 ruling, stated, “Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

Lemkin has held nearly a dozen public discussions in various parts of California and western Massachusetts. Locally, he’s held one at the Jones Library in Amherst as well Forbes Library.

“I want to present this as a human issue rather than a political issue,” Lemkin said, noting that he does not identify as either a Republican or Democrat. “I believe in justice and fairness, and that is not necessarily a political issue. As soon as it becomes partisan, then this division, this wound that this country is experiencing, gets wider and wider.”

During Lemkin’s recent discussion at Forbes, he delved into the many ways that the removal of preclearances from the Voting Rights Act has affected voters in states with histories of voting discrimination.

On the same day that the court made its ruling, many began taking steps to enact laws that removed provisions such as online voting registration, early voting, Sunday voting and same day registration.

Additionally, Lemkin said the closing of polling stations has contributed to a significant drop off in voting.

A study conducted by the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights found that there were 868 fewer polling stations in 2016 when compared to 2012 in the United States.

In Phoenix’s Maricopa County, election officials reduced the number of polling places from 200 to 60 from 2012 to 2016, leaving one polling place per 21,000 registered voters, according to the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law.

According to the Voter Participation Center, more than 35 percent of all eligible Americans — over 73 million citizens — are not registered to vote. People of color account for 30-40 percent of unregistered voters, millennials 39 percent, and unmarried women 32 percent.

“There is massive injustice in this country going on, and there is no more efficient way to affect change in the political realms than to vote,” Lemkin said. “My interest is to talk to as many students as I can. This is an educational mission about voter suppression and voting rights. It’s about getting people who can register to vote to actually register and vote.”

On Saturday, Oct. 20, Jim Lemkin will hold a public discussion at Williamsburg’s Meekins Library from 1 p.m. to 2:30 p.m.

Luis Fieldman can be reached at lfieldman@gazettenet.com